By Anna Maria Barry-Jester FiveThirtyEight

This is review No. 4 of four in the second round of our competition. Each review will compare four burritos, with my favorite advancing to the third and final round.

This week we journey from Boston to Alabama and from San Francisco to El Paso to determine the fourth entrant in the Burrito Bracket’s final round. If my Round 1 opinions hold, it will be a close match between El Paso’s Delicious Mexican Eatery and San Francisco’s Taqueria Cancún. California already has two restaurants in the finals; does it rate a third?

Taqueria Cancún

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

A few days after my second Burrito Bracket tasting at Taqueria Cancún, I spoke with one of the owners, Gerardo Rico (the other owner is Pedro Grande, two names so perfect I first thought they must be pseudonyms). He was hesitant to be interviewed, or to be more accurate, he declined when I first asked. He told me he was “dealing with a little problem,” and talking to the press wouldn’t help. I feared the worst, and asked if he could at least confirm a few details about the history of the restaurant. And so, Rico sat down with me at one of the long picnic benches, sighed, and speaking in Spanish in a quiet, tired voice, began to explain his predicament.

Some famous guy (comedian Marc Maron) had written about the restaurant on Twitter:

Taqueria Cancún opened in 1993, more than a decade after Rico and Grande moved to the United States (from Mexico and El Salvador, respectively). Before they opened their spot on Mission and 19th, they worked at a taqueria a few blocks up the street, a joint that would eventually be their competitor in the first round of the Burrito Bracket: El Farolito. The owner encouraged Rico to go out on his own, and they remain friends today, according to Rico. When I asked about Taqueria Cancún’s recipes, he told me they are a blend of El Farolito and food he knew growing up, with the exception of Cancún’s famous vegetarian and chicken burritos. Rico and crew don’t steam the tortillas, which he says makes all the difference for the texture of the vegetarian bundle. The chicken is marinated and then grilled with an iron, which makes it juicier than some of its Mission Street counterparts.

As our conversation went on, Rico explained that the crowds weren’t his only woe. The taqueria has been without a lease for more than a year, since the building’s owner, whom Rico described like a patron saint, passed away. The owner’s family isn’t sure what to do with the place, so Cancún is currently on a month-to-month lease. I asked what would happen to the restaurant. “Who knows,” he said, taking a deep breath.

We chatted for a while before saying adios. I left feeling slightly honored yet horrified that I’d been a contributor to Rico’s distress and exhaustion. I also worried for the future of the restaurant.

The mere mention of the name Taqueria Cancún evokes great emotion in its most fervent followers. One loyal fan even wrote this plea that it not win the bracket, fearing national acclaim would ruin the place.

And so, dear readers, it seems I must beg you not to go to Taqueria Cancún. Don’t wait in line beneath the colorful paper cutout banners hanging from the ceiling. Don’t gaze upon the statue of the Virgin Mary and the murals of waterfalls and jungle scenes while you wait in line to order an al pastor. Don’t smell the sweet pineapple, chile and char as you peel back the tinfoil from the heavy bundle. Don’t eat the perfectly distributed innards so fast that bright red juice runs down your face. Don’t load up on calories with the rice, or savor the lard-laden pinto beans and thick slices of avocado. And whatever you do, definitely don’t get up and order more when you’ve finished that last bite.

On a more serious note, the burrito scored lower this round because of abundant rice and oil. Though still a food fit for kings, this was a greasy yet dry burrito — a problem I have encountered occasionally in the past. Those few points put Cancún’s prospects of advancement in serious peril.

Little Donkey

HOMEWOOD, ALABAMA

Five minutes into a conversation with Josh Gentry, chef and founding partner of Little Donkey, I realized he was interviewing me. In his Alabama drawl, he asked about my exercise routine, how I’d enjoyed my trips to Little Donkey, how much longer I’d be on the road. He’s curious, thoughtful and laid back, with a bit of stereotypical Southern charm. In other words, he is a lot like his food.

Gentry had worked at Jim ‘N Nick’s — the premier restaurant of the Fresh Hospitality group to which Little Donkey belongs — for nearly a decade when owner Nick Pitakis decided it was time to give a Mexican restaurant a go. Pitakis told me Gentry was the missing ingredient. As with the other 80 restaurants Pitakis owns, there is no freezer at Little Donkey. Everything is made fresh, and the kitchen is open, so customers can see how the magic happens.

Gentry told me he fell in love with Mexico partly because Spanish was the only subject in which he excelled in high school. During a study-abroad trip to Mexico, he was placed in a home in Cuernavaca. The host family’s son, who was in the military, was killed the day before Gentry arrived. So while the family grieved, he spent his time at the restaurant the family owned, and was moved by the vibe.

Of cooking, he said, “It’s not like you choose it; it’s just all I can do.”

That restaurant was the inspiration for the atmosphere at Little Donkey: neighborhood bar meets social club meets bistro. When I made my visit for Round 2 of the bracket, the patrons next to me at the bar chatted with the bartender. “This place is like an island — it’s where you want to be, all the time, just relaxing,” one of them said.

The restaurant has had its share of failures. It was a huge point of pride for Gentry to have chilaquiles, one of his favorite Mexican dishes, on the menu. “But our guests revolted,” he told me, annoyed that their “nachos were soggy.”1

They had a similar problem with the chips served at the beginning of each meal. Gentry wanted the thick rugged triangles he’d fallen in love with in Mexico, but his guests wanted something thinner, closer to what you can buy at the grocery store. “We literally had a conversation about whether or not we wanted to stay in business, based around those chips,” he recalled. Gentry thinks Little Donkey has struck a good balance between his personal vision and what the neighborhood is ready for. “One day I will feed people chilaquiles,” he told me just before we hung up the phone. A man can dream.

On my second visit, I ordered an adovada burrito, just as I had done in Round 1 (I ordered a different side this time, elote, which was mushy and doused in too much mayonnaise, but the heavy-handed spices were just right). The tortilla came out charred and flaking off on the outside. Although the burrito was a little clumsier (the folds didn’t come in at perfect right angles and the bundle seemed to have been flopped on the plate), its size was slightly less intimidating, and the taste was just as good. Smoky pork slid apart in a stew of pinto beans and tomato. The guacamole was fresh (I watched as some was made behind the counter) with chunky avocado, tastier than on my previous visit now that avocados were in season. Overall, the burrito was a little heavy, but it’s hard to imagine a much better marriage of American Southern and Mexican cuisines.

Delicious Mexican Eatery

EL PASO, TEXAS

I was standing on the side of Franklin Mountain, looking down over El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, when Ray Borrego returned my call. I’d been looking at the U.S.-Mexico border, drawn in cement (since the Rio Grande defines the border between the two countries, it was cemented to keep the border from shifting with the river. It’s empty this time of year). Borrego’s family has lived on both sides of that cement line, he told me. His father was born in Zacatecas, his mother in Guadalupe, Nuevo León. They met in Mexico City and moved to Juarez after they were married. By the time Borrego was born, the family was already living in El Paso.

“They opened it to keep Mom busy, but it turned out to be a success,” Borrego told me, recounting the history of Delicious Mexican Eatery. The restaurant opened in 1978. Borrego now owns the place, as well as a second location on the campus of the University of Texas at El Paso, called Delicious Mexican Express, which serves food to go. The original location has garnered so many local awards he can’t remember them all, but he recounts a few to me in a voice both humble and proud. One of his favorites was a proclamation from the city of El Paso calling the family restaurant the most authentic Mexican food in town.

I asked him what “authentic” means to him. I’m not usually a fan of the word, which I believe has an air of superiority; I prefer the term “traditional” when referring to food that’s closest to its origins. Borrego’s definition of the word authentic, however, gave me food for thought: “People usually say, ‘It tastes like what my abuela makes.’ Or, ‘It’s as good as my mom’s. It tastes like a home-cooked meal.'”

Fair enough, as the food served at the restaurant is what he grew up on. He remembers eating burritos after school, or taking two to eat at lunchtime. They were always small, filled with a guisado (the Spanish word used to describe thick stew-like dishes and casseroles). Sometimes they would add refried beans, but mostly these were no-frills burritos. Borrego sees adding rice and other ingredients as turning the traditional Mexican snack into a rolled-up meal. He’s also adamant that burritos are in fact Mexican food.

In every way, the burritos of El Paso are much humbler than the famous Mission-style offering. Handmade tortillas are filled with simple, elegant ingredients. Everything is prepared fresh to order, and $3.50 is on the high end of the price scale. The border city has none of the blogger hype so pervasive in Internet-loving San Francisco. But you can taste the simplicity of the burrito’s origins in these delicate beauties.

Even though I gave it a score of 92, I undervalued Delicious on my first visit for the Burrito Bracket. I had spent the day eating burritos in Ciudad Juarez, and food generally tastes better in Mexico (I will explore the reasoning behind this statement in a future article). I was unfairly hard on Delicious as a result.

In my first review, I described the chile verde as pork and green chile. Borrego politely corrected me, letting me know that the tender, pale meat is actually beef that’s been cubed and cooked at length with salt, pepper and garlic. The restaurant uses Hatch green chiles, an important detail for many local customers proud of the area’s famed produce.

My burrito, wrapped in logo-emblazoned wax paper, was even better on the second visit. The tortilla was tasty, hand-pulled and grilled on the comal as I ordered. But it was the chile verde that really stepped up its game: Meaty green chile infused the stewed potato and tender beef with swift, intense heat. Juices ran down the side of the burrito, softening the second half of the tortilla. The bouquet of flavors tasted fresh from the earth, with unbelievable depth for such a seemingly simple filling.

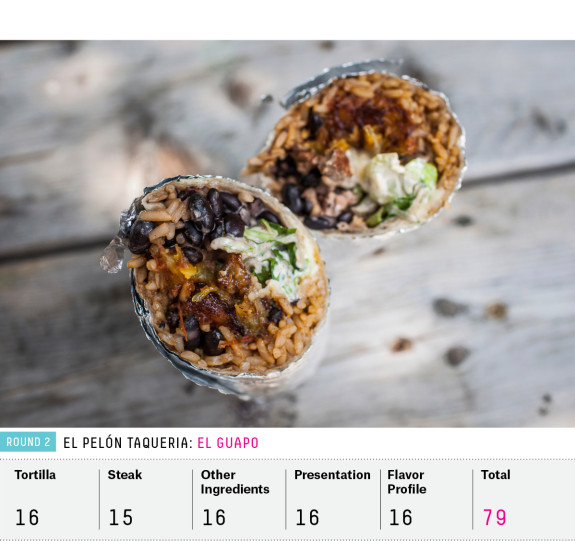

El Pelón Taqueria

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

“Coming from Cape Cod, you can fish or open a restaurant,” Jim Hoben told me. He opted for both.

The bald, mustachioed owner of El Pelón Taqueria in Boston opened a vegetarian restaurant in the 1990s, but the city wasn’t ready for veg. As he looked for his next idea, he thought about how most of the kitchen workers he knew were Latino, no matter the cuisine. Hoben is a restaurateur, not a chef, and sees his staff as essential. “I wanted to just get out of the way,” he told me by phone, “and let them cook what they know how to cook.”

El Pelón Taqueria opened in 1998, in the neighborhood where Hoben lived at the time: Fenway. The proximity to the Red Sox ballpark wasn’t strategic; in fact, it actually hurt business at first because many Boston residents steer clear of that area, especially on game days. Slowly word spread, and business picked up accordingly until 2009, when a fire raged through the block of restaurants where El Pelón is located. Hoben soon got a store running east of the original location, in nearby Brighton. It was an instant success, and steady business helped him reopen the original location. The two restaurants keep him plenty busy.

The restaurant is most famous for its El Guapo burrito (though Hoben and team are proud of the fish burritos they make as well). It will dismay some Red Sox fans to know that the signature burrito isn’t actually named after Rich “El Guapo” Garcés. “If you ask any of my workers, they’ll say it’s named after them,” Hoben told me. But like many items on the menu, it was born of experimentation by employees who are allowed to eat whatever they want during their shifts. The name just fit.

On my second visit to El Pelón, the handsome burrito looked just like it had on my first encounter. Crisp, fried, sweet plantains lay in waiting like gold nuggets amid steak that was a little too tough. The burrito was sauced more heavily with the fire roasted salsa and sour cream, making it a juicier delight, an improvement from the previous visit. Salty Mexican rice and black beans played perfectly with sweet plantains.

This isn’t the greatest burrito in America, but it’s probably the best in the Bean, and some of the best food in walking distance of Fenway Park.

Final Decision

I’m not sure whether it will be to the chagrin or the elation of loyal Taqueria Cancún fans, but Delicious Mexican Eatery is advancing to Round 3. This correspondent is relieved that the competition won’t come down to a referendum on the inclusion of rice in Mission-style burritos.